ADAMS COUNTY HUMANE SOCIETY

Cat Health Issues

Viruses

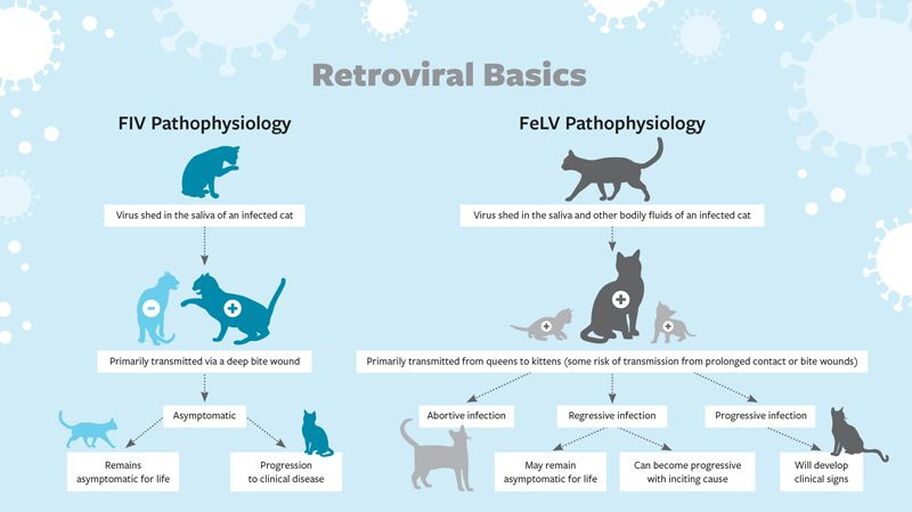

Understanding feline retroviruses, including Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) and Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), is critical to the health of your cat population.

FIV is primarily transmitted through deep bite wounds, when the virus enters the bloodstream of the cat. Unsurprisingly, unneutered free-roaming toms, who are the most likely to fight over territory and mates, have the highest incidence.

In a study published in 2014, researchers followed a group of 130 FIV-negative cats and eight FIV-positive cats, all of whom were sterilized and mingled freely in a rescue environment. After several years, despite mutual grooming and “minor episodes of aggression,” none of the negative cats tested positive.

FeLV, which is found in the blood, saliva and other bodily fluids of an infected cat, is most commonly transmitted from an infected queen to her kittens. Healthy adult cats have partially protective natural immunity to the virus. However, there is a small risk of spread through casual contact, such as mutual grooming or sharing water and food bowls.

While there are plenty of anecdotal reports of noninfected cats cohabitating with FeLV-positive cats without contracting the virus, most experts recommend not mixing the two populations. It’s uncommon to transmit FeLV in sterilized adult cats. It takes prolonged intimate contact, and even then it’s uncommon. Cats housed next to each other in cages are not going to give FeLV to one another, even if they sneeze on the other.

Several studies show that FIV cats have comparable life spans to noninfected cats, but the answer for FeLV cats is more complicated.

The data so far indicates a significantly shorter than average life expectancy, but with tremendous variability among individual cats. Some cats who initially test positive will essentially buck off the infection and later test negative. Some, showing what’s called a “regressive” infection, will continue to test positive with low levels of virus but could remain healthy into their teens and 20s. Some will have a “progressive” infection and succumb to a virus-related illness at an early age. And some have test results that flip flop from month to month.

The feline distemper vaccine is a combination vaccine that protects your cat from feline viral rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleukopenia.

Rhinotracheitis/Calicivirus

Feline rhinotrachetis and calicivirus (feline herpes virus type I) are responsible for 80-90% of infectious feline upper respiratory tract diseases. Most cats are exposed to either or both of these viruses at some time in their lives. Once infected, many cats never completely rid themselves of virus. These "carrier" cats either continuously or intermittently shed the organisms for long periods of time -- perhaps for life -- and serve as a major source of infection to other cats. The currently available vaccines will minimize the severity of upper respiratory infections, although none will prevent disease in all situations. Vaccination is highly recommended for all cats.

Feline Panleukopenia in the past was a leading cause of death in cats. Today, it is an uncommon disease, due in large part to the availability and use of very effective vaccines.

What is feline panleukopenia?

Feline panleukopenia (FP) is a highly contagious viral disease of cats caused by the feline parvovirus. Over the years, FP has been known by a variety of names including feline distemper and therefore gives the name to the feline distemper vaccine. It infects and kills cells that are rapidly dividing, such as those in the bone marrow, intestines, and the developing fetus. Infected cats usually develop bloody diarrhea, anemia and are more likely to be infected with other illness.

How can you tell if a cat has FP?

The first visible signs an owner might notice include generalized depression, loss of appetite, high fever, lethargy, vomiting, severe diarrhea, nasal discharge, and dehydration. Sick cats may sit for long periods of time in front of their water bowls but not drink much water. Cats are very good at hiding disease and by the time a cat displays the signs of illness, it may be severely ill. Therefore, if any abnormal behaviors or signs of illness are observed, it is important to have your cat examined by a veterinarian as soon as possible. FP may be suspected based on a history of exposure to an infected cat, lack of vaccination, and the visible signs of illness. FP is confirmed when the feline parvovirus is found in the blood or stool.

How do cats become infected with the virus that causes FP?

Infection occurs when cats come in contact with the blood, urine, stool, nasal secretions, or even the fleas from infected cats. A cat can also become infected without ever coming in direct contact with an infected cat. Bedding, cages, food dishes and the hands or clothing of people who handle the infected cat may harbor the virus and transmit it to other cats. It is, therefore, very important to isolate infected cats. The virus that causes FP is difficult to destroy and resistant to many disinfectants. Pregnant female cats that are infected with the virus and become ill (even if they do not appear seriously ill) may give birth to kittens with severe brain damage.

Which cats are susceptible to the virus?

While cats of any age may be infected with the feline parvovirus that causes FP, young kittens, sick cats, and unvaccinated cats are most susceptible. The virus has appeared in all parts of the United States and most countries of the world. Kennels, pet shops, animal shelters, unvaccinated feral cat colonies, and other areas where groups of cats are housed together appear to be the main reservoirs of FP. During the warm months, urban areas are likely to see outbreaks of FP because cats are more likely to come in contact with other cats.

How is FP treated?

The likelihood of recovery from FP for infected kittens less than eight weeks old is poor. Older cats have a greater chance of survival if adequate treatment is provided early. Since there are no medications capable of killing the virus, treatment is limited to supporting the cat's health with medications and fluids until its own body and immune system can fight off the virus. Without such supportive care, up to 90% of cats with FP may die. Once a cat is diagnosed with FP, treatment may be required to correct dehydration, provide nutrients, and prevent secondary infection.

How can FP be prevented?

Cats that survive an infection develop immunity that protects them for the rest of their lives. Mild cases that go unnoticed will also produce immunity from future infection. It is also possible for kittens to receive temporary immunity through the transfer of antibodies in the colostrum ? the first milk produced by the mother. How long this passive immunity protects the kittens from infection depends upon the levels of protective antibodies produced by the mother. It rarely lasts longer than 12 weeks. "An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" definitely rings true for FP - preventing infection is more effective than treating an infected cat. Today, there are vaccines that offer the best protection from feline parvovirus infection. The vaccines stimulate the cat's body to produce protective antibodies. Later, if the vaccinated cat comes in contact with an infected cat, its body will fight off the infection because of those same antibodies produced in response to the vaccine. The vaccines are effective for prevention of FP but they cannot treat or cure an unvaccinated cat once it becomes ill. Vaccines must be given before the cat is exposed and infected. Most young kittens receive their first vaccination between six and eight weeks of age and follow-up vaccines are given until the kitten is around 16 weeks of age. Adult vaccination schedules vary with the age and health of the cat, as well as the risk of FP in the area.

Thank You! |

1982 11th Ave, Friendship, WI 53934

Phone: 608-339-6700 [email protected] License #266944-DS Click Here to Contact Us |

|